Reinforcement Learning as Probabilistic Inference - Part 1

This series of posts explores the intersection of reinforcement learning and probabilistic graphical models, delving into the optimization of policies through inference, bridging the gap between planning and decision-making under uncertainty.

This is a series of posts to formalize the underlying similarities in algorithms for Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Generative Models (GMs), which on the surface have distinct formulations for tasks of different nature and explore their integration. The long term goal is to take the best of the two frameworks for decision making in physical environments. Something along the lines of generate policies that are adaptable and generalizeable, without having to collect large corpus of data particular to the task, while building on foundation models, now prevalently trained as generative models.

The Best of Both Worlds

While Reinforcement Learning (RL) isn’t necessarily coined as generative, and it is not developed for generative tasks, it is used to generate policies that are adaptable and generalizeable to unseen situations. It is an agentic frame for solving decision making problems that does not require data apriori but the agent goes through trial and error while interacting with the environment. In this process, a policy, a mapping from state to action, that would maximize the expected cumulative rewards, which typically aligns with the given task across the trajectory, is learned. The premise is there is a dynamic of the environment, and some kind of decision making in that environment of which one is better than the other. Through the agent interactions, the dynamics and policy are learned simultaneously (model-based RL make the learning of the dynamics explicit, while for model-free RL, the learning of the dynamics is implied in the direct policy learning).

On the other hand, Generative Models (GMs) are commonly trained with supervised-learning, where the model is learning a probablistic distribution from existing data. The hope is that samples from this trained distribution align with the underlying features of the existing data i.e. looks like an image in the real world, while not being directly from the existing data, but can also align with the task i.e. generate an image that aligns with the text prompt.

At this point, many advancements of GMs are being made by building on top of foundation models which are trained on a corpus of data with a lot of compute. Prompting, finetuning models is all a natural path because the problems are framed as probabilistic models to start with, and methods of conditioning and inference from such models are well known. On the otherhand, RL, by its nature of learning a decision making policy, has potential to be adaptable and generalizeable to unseen variations of the task. This has been explored with a certain suite of tasks such as robotic control, games, but recent works have questioned its robustness [1] expecially for tasks beyond the conventional realm [2]. These works show that RL algorithms have overfitted such well-known tasks and it is still apparent that for custom task the approach of training proprietary environments from scratch is still common. One explanation for this is that RL is striving to solve a much harder task; making a sequence of decisions to reach a goal vs emulating a goal. This requires the learning of both the dynamics of the environment relative to the task, and finding the best decisions to make which the approach of supervised-learning on existing data is not readily applicable.

How can RL and GMs relate?

Some characteristics of RL and GMs that I find to relate to each other:

RL shares a similar frame of making sequential predictions while referring to previous states with autoregressive transformers which have advanced GMs significantly. Although the difference is that the mechanism of RL is based on look-ahead approximations as opposed to tokens and attention used in transformers.

Diffusion models also share the underlying idea of RL that factorizes a complex problem into smaller sequential steps in time by leveraging the premise of the Markov Decision Process (MDP) where the current state conditions on the previous state.

For both approaches, what is learned in the end are parameterized distributions. While RL does not require data upfront, each trial-and-error of the agent within the environment equates to a training data instance in supervised learning, so in a sense it is generating training data as it goes. Reward signals used within the training of RL agents, can be equated to the conditioning of a trained GMs for a specific outcome. The difference is that with RL the distribution being trained is a distribution of trajectories, from which we can derive a promising policy, and GMs learn distributions of generated instances.

Why do we want to formally connect RL and GMs?

The ultimate goal of RL is to estimate stationary policies or single-step models. We want to explore the possibility of reframing decision making problems, especially those that are across a temporal sequence, to be solved with probabilistic distribution matching frames that have successfully trained GMs. The connection between reinforcement learning and inference in probabilistic models is not obvious. However, formalizing a sequential decision making problem as probabilistic inference in principle allows us to bring to bear a wide array of approximate inference tools, extend the model in flexible and powerful ways, and reason about compositionality and partial observability [6]. Especially with the advent of high-capacity sequence prediction models that work well in other domains, such as natural-language processing, formulating the task with probabilistic modeling has become very promising.

More specifically, probablistic modeling can allow us to break away from the restrictive structure of RL. A strong underlying causal structure of the trajectory data in RL is that the dynamic is Markovian; the current state relies only on the previous state. While this structure is the backbone of RL which allows for optimization with theoretical guarantees, it is often the case that it is more advantageous to employ various structures that are not only causal (where the current state depends on the previous state) but also anti-causal (where the current state depends on the future state). Ideally, we would want the flexibility to use structured information that better fit the objective of the task i.e. planning, and also perform better on sparse reward, long horizon tasks where the local structure of the MDP is insufficient. Research in the RL community have extensively explored this, but in its current state methods are not easy to implement, requiring extensive tuning to the task. The expectation is if we can frame and solve such tasks as a probablistic models, not only would we be able to take advantage of causal and anti-causal structure more flexibly, but we can also leverage existing foundation models to solve complex decision-making problems that were difficult to solve with only RL.

Decision Making as a Probabilistic Graphical Model

Decision making problems (formalized as RL or optimal control), can be viewed as a generalized Probabilistic Graphical Model (PGM) augmented with utilities or rewards, that are viewed as extrinsic signals. In solving these problems, one common approach is to model the underlying dynamics as a probabilistic model e.g. with model-based RL, and in a distinct process, e.g. trajectory optimization an optimal plan or a policy is determined.

What are Probabilistic Graphical Models (PGMs) and why do we want to use them?

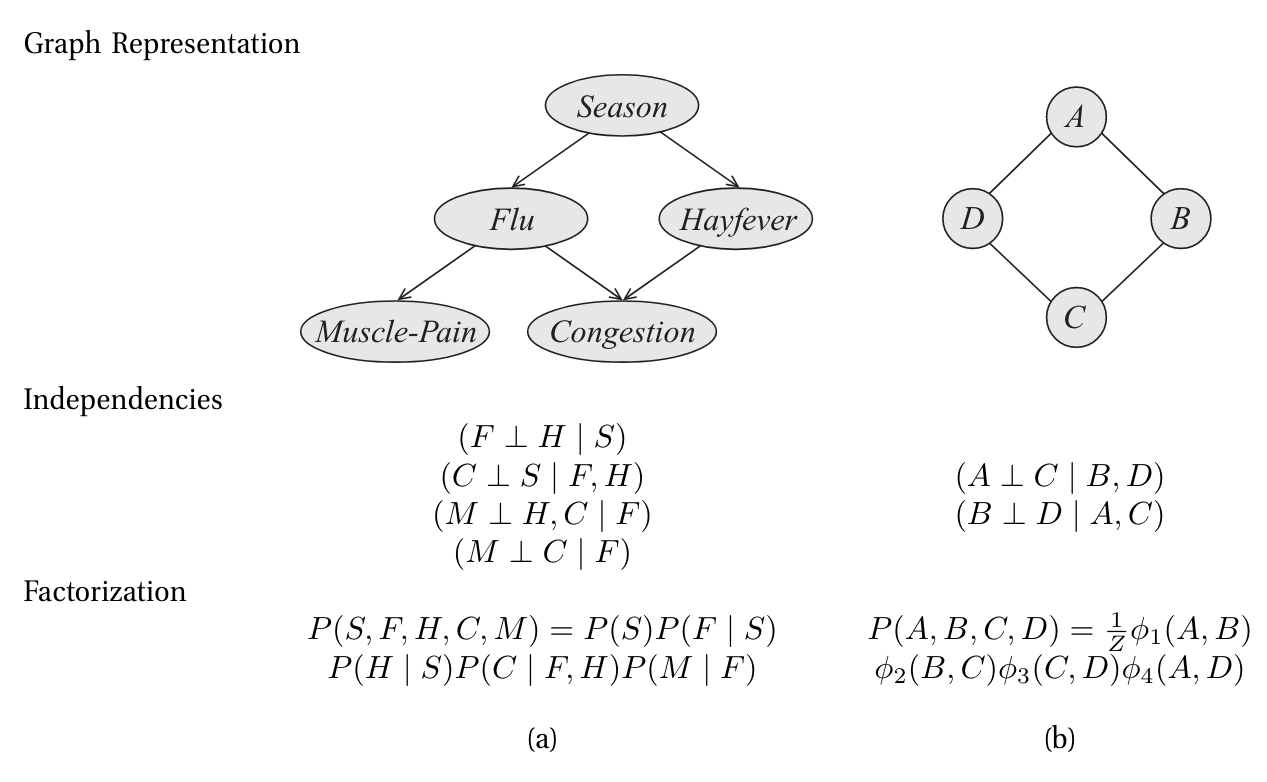

Probabilistic graphical models use a graph-based representation as the basis for compactly encoding a complex distribution over a high-dimensional space. In this graphical representation illustrated below, the nodes (or ovals) correspond to the variables in our domain, and the edges correspond to direct probabilistic interactions between them.

In the framework of PGMs, it is sufficient to write down the model and pose the question, and the objectives for learning and inference emerge automatically.

Conventionally, determining an optimal course of action (a plan) or an optimal decision-making strategy (a policy) is considered a fundamentally distinct type of problem than probabilistic inference, although the underlying dynamical system might still be described by a probabilistic graphical model.

References

- C. Benjamins et al., “Contextualize Me – The Case for Context in Reinforcement Learning,” 2023.

- J.-H. Cho, V. Jayawardana, S. Li, and C. Wu, “Model-Based Transfer Learning for Contextual Reinforcement Learning,” 2024.

- “Deep Learning in a Nutshell: Reinforcement Learning,” NVIDIA Technical Blog. https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/deep-learning-nutshell-reinforcement-learning/, 2016.

- A. Torralba, Foundations of Computer Vision. in Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2024.

- waldoalvarez, “Own work.” 2017. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59364518

- S. Levine, “Reinforcement Learning and Control as Probabilistic Inference: Tutorial and Review,” 2018.